Travel

Tide and joy: New Brunswick’s culinary delights

From learning the secret of hand-dipping chocolate to dining on lobster aboard a cruise, New Brunswick’s growing food scene boasts plenty of new culinary experiences

- 622 words

- 3 minutes

Travel

From learning the secret of hand-dipping chocolate to dining on lobster aboard a cruise, New Brunswick’s growing food scene boasts plenty of new culinary experiences

Travel

Discovering beauty and resilience on the world’s second-largest barrier reef

Travel

Named after the south star, Octantis is Viking’s first expedition ship, which incorporates visits to Indigenous communities, supports environmental protection and more

Travel

From sea caves to deserts, this three-day guide offers the perfect itinerary to make the most of this corner of California

Travel

The first Marriott-branded all-inclusive resort offers outstanding hospitality and exquisite food options in a beloved sun destination

Travel

Travel

Travel

Travel

Travel

Travel

Travel

After a challenging ski season as a result of warmer weather, winter is alive and well at SilverStar Mountain Resort, along with a few surprises

Travel

An off-grid eco-friendly resort, only accessible by boat or seaplane, turns out to be the unexpected perfect “babymoon” destination for nature’s lessons in the wildest maternal instincts

Travel

Each community has its own personality — and so do their eateries

Travel

The RCGS Fellow and Travel Ambassador discusses her experience in “Canada’s Galapagos” with Maple Leaf Adventures

Travel

On the coast of B.C.’s mainland awaits an immersive experience on the water’s edge, where tourism can be an act of reconciliation

Travel

Here & There host and producer Liz Beatty tests her own mettle on backcountry peaks with CMH Heli Skiing and Summer Adventures. Along the way, she introduces us to some amazing women who’ve helped make mountaineering what it is today.

Travel

Robin Esrock investigates the growing trend of alcohol-free wine, beer and spirits

Travel

Mount Engadine Lodge is the perfect base for a slew of spectacular mountain trails

Travel

Here & There host Liz Beatty takes us on a journey of revelations that uncovers the other half of the story of one family’s part in the birth of Canada’s New Scotland. It’s a road trip deep into a sea-change moment happening across Nova Scotia, and to the precise intersection point of two cultures and two families that no one saw coming.

Travel

Travel

Travel

Travel

Travel

Travel

Travel

Robin Esrock heads to Whistler to tick the world’s fastest sliding track off his Canadian bucket list with a special appearance from Olympic champion Jon Montgomery

Travel

Renowned for its world-class beaches, ecotourism and historical sites, this tropical paradise exudes relaxation, making it the perfect destination to unwind and escape from everyday life

Travel

It may be the Theme Park Capital of the World, but there is plenty of adventure in Orlando beyond the amusement parks

Travel

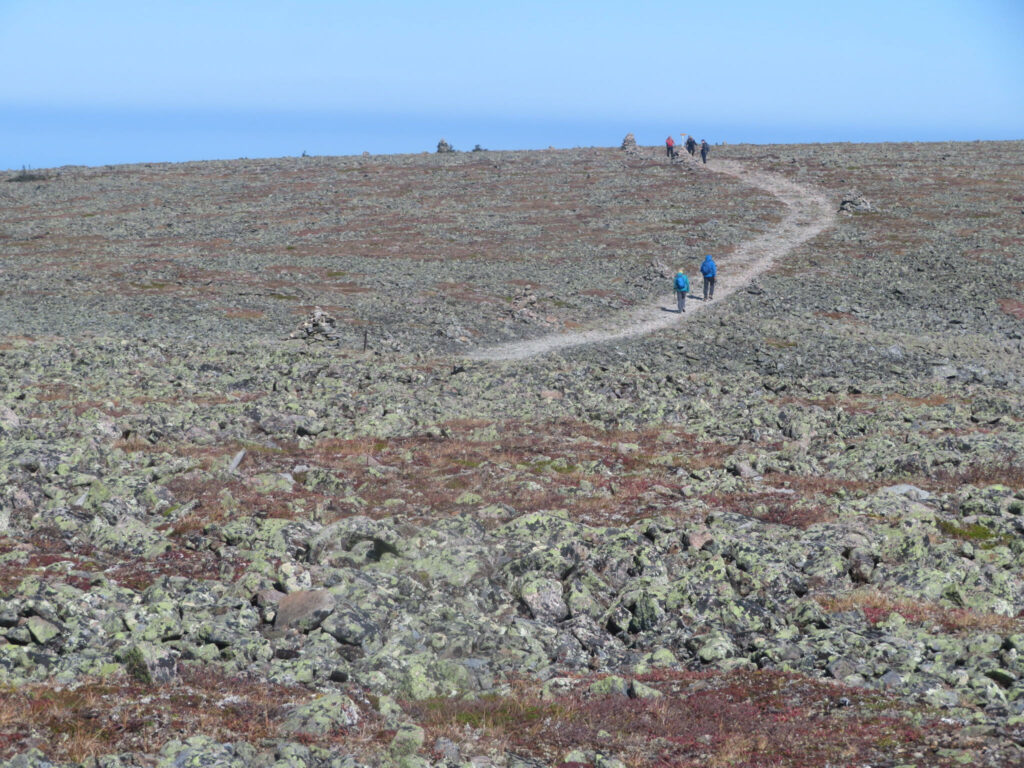

With solar activity expected to peak in 2024, there’s never been a better time to see the northern lights. Here’s how to do it in the “aurora capital of North America.”

Travel

Experiencing the world’s largest carnival during a week of celebration, social unity, parades, colourful fashion and of course, partying

Travel

Seeing iconic landscapes before they fade away may be accelerating their demise. Can we square the circle on making these trips sustainable?

Travel

Offering something for everyone, this 584-kilometre wind-swept shoreline is packed with historical sites, isolated beaches, quiet seaside towns and more

Travel

The ultimate rainforest retreat complete with eco-adventures, hands-on education and adrenaline-inducing activities amidst tropical jungle scenery

Travel

Microdosing psilocybin, plus three other ways to relax and unwind by the crystal-clear waters of western Jamaica

Travel

From South African penguins and Canadian bears to Australian wombats and Bolivian pumas, Robin Esrock introduces inspiring wildlife sanctuaries where volunteers make all the difference

Travel

From ice chutes and air canons to floating hot tubs and Canada’s tallest rollercoaster, Robin Esrock invites you to buy the ticket, take the ride and scream to your heart’s content

Travel

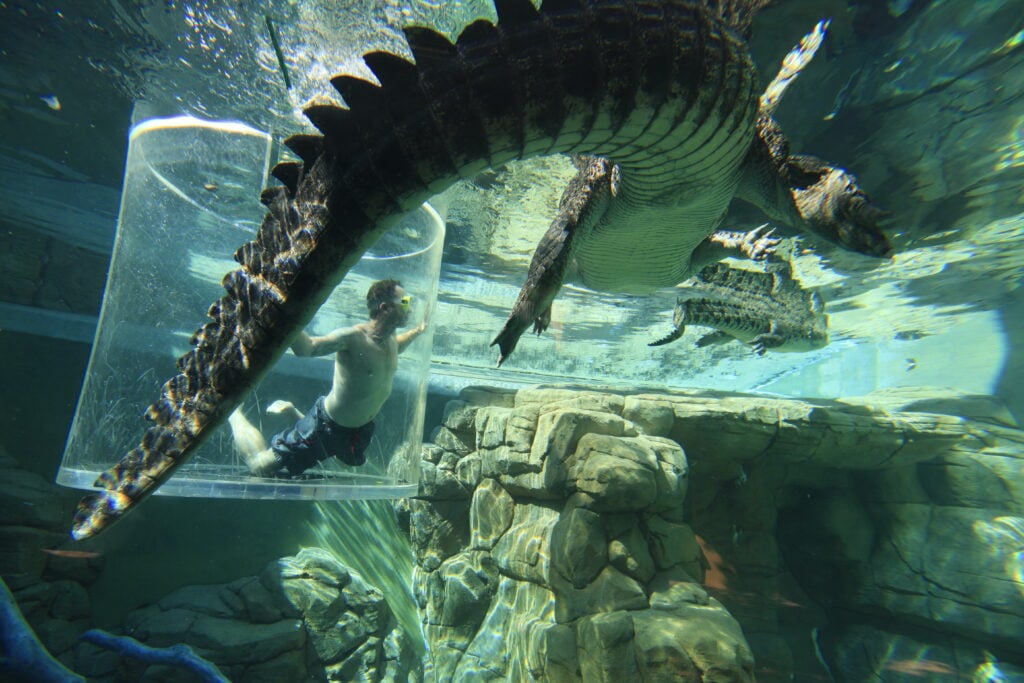

Up close and personal with the man-eaters of Australia’s Northern Territory

Travel

Making authentic connections with a local taste of food, culture, and nature

Travel

Located in the foothills of the Rockies, this Indigenous experience invites you to engage with Indigenous outdoor traditions and reconnect with nature in a new way

Travel

Avoid the crowds and discover frozen canyons, scenic lakes and hearty cuisine in this epic Rocky Mountain town

Travel

An inside look at Good Knights medieval-themed glamping experience — complete with sword fighting, axe throwing, archery and more

Travel

A guide to the annual Jasper Dark Sky Festival — and what you can learn when you gaze skywards.

Travel

Formed in varying shapes and sizes, these glacier caves create the “perfect playground for photographers”

Travel

Inspired by the trees that line the misty mountains of Vancouver’s coastal rainforest, the DOUGLAS offers a multi-faceted city escape

Travel

A three-day guide to exploring the diverse culture, rich history and beautiful beaches of America’s first settlement

Travel

Where to stay, what to do and how to make the most out of your time in Costa Navarino

Travel

From slopes to ski lift passes and resorts to spas, the cost of a ski trip to Switzerland isn’t much more expensive than a visit to the Rockies

Travel

For almost a century, Magnetic Hill has boggled the minds of visitors. Here’s a closer look at what makes this magical spectacle so intriguing.

Travel

Once an enormous coral reef, these magnificent mountains are now one of Italy’s main outdoor attractions

Travel

*Okay, just six — but it’s a start toward exploring this expansive border-straddling region of rocky islands, sparkling coves and hidden history

Travel

An exclusive look at SailGP aboard Canada’s F50 catamaran yacht and how this international sailing competition is keeping sustainability in mind

Travel

At British Columbia’s Purcell Mountain Lodge, guests can partake in skiing and snowshoeing and then end the day with a well-deserved three-course dinner

Travel

From New York’s iconic Statue of Liberty to the famous Christ the Redeemer in Rio de Janeiro, these are some of the world’s most captivating statues

Travel

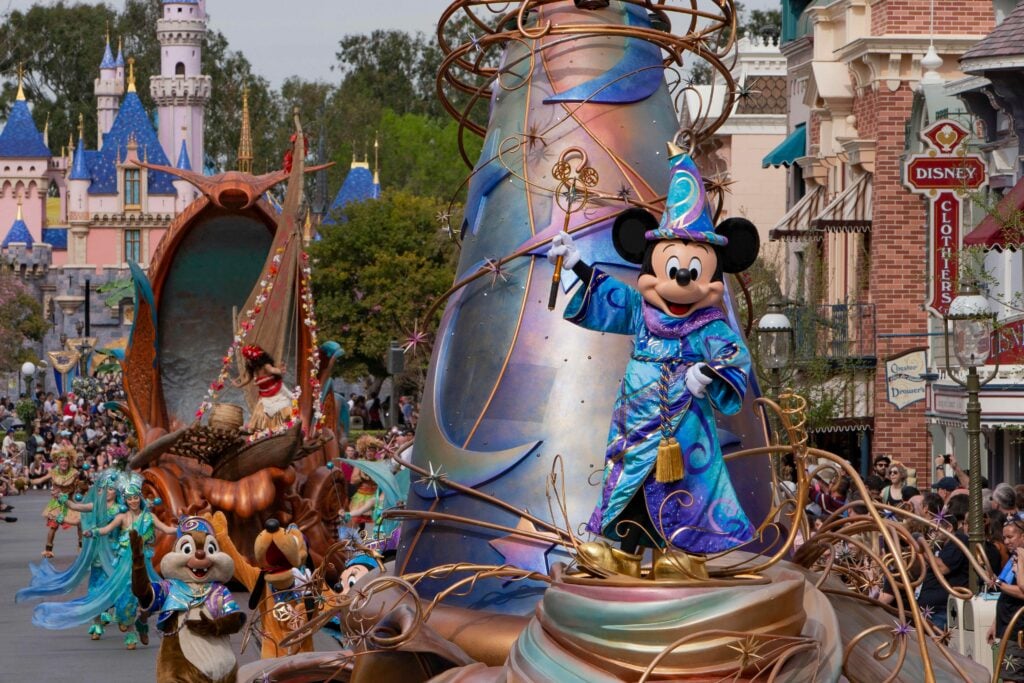

How to make the most out of your visit to Disneyland, plus all the tips and tricks needed to ensure you and your family have a positive experience

Travel

Wine, cheese and all the rest: highlights from Quebec’s sustainable culinary industry

Travel

Following the St. Lawrence’s winding course through Quebec delivers a feast of history, culture and food

Travel

A history of Alberta’s quirky Burger Baron restaurant chain

Travel

Expect the unexpected in the Kootenays, including a visit to an epic frozen waterfall

Travel

A couple’s guide to taking in the wine, food and unique desert scenery of Osoyoos

Travel

Night skiing under the direction of Olympic legend Nancy Greene Raine

Travel

Fly fishing for steelhead trout and salmon in Northern B.C.’s bucket list angling destination

Travel

A tired mom’s quest for rest on a solo road trip around southern Vancouver Island

Travel

After years of waiting to see the aurora borealis, Robin Esrock recounts his experience viewing these dancing lights with his father in Yellowknife

Travel

RCGS Travel Ambassador Carol Patterson recounts her experience observing these legendary birds on a Canadian Geographic Adventure

Travel

Susan Nerberg embarks on a deeply personal tour of Tromsø, taking part in Sámi Week as a means to better understand her own Sámi roots and culture

Travel

Les villes et villages situés le long de la Promenade du sentier Fundy s’associent pour donner la priorité à la communauté et à l’environnement, alors que la région partage ses paysages enchanteurs avec le monde entier.

Travel

Cities and towns along the Fundy Trail Parkway are banding together to prioritize community and the environment as they share their magical landscape with the world

Travel

From modern works of sculpture to remnants of ancient civilizations, Italy’s Umbria region is rich in cultural heritage

Travel

Experiencing living history at Métis Crossing, a one-of-a-kind destination for Métis people to share Métis stories

Travel

A three-day guide on where to stay, what to do and how to make the most out of your time exploring Western Newfoundland

Travel

A heartwarming story along one of the most spectacular urban hikes in the world with Great Canadian Trails

Travel

Immerse yourself in Viking archaeology and Basque whaling history while taking in Newfoundland’s scenic coastline and incredible geology

Travel

Rocking and rolling across the Atlantic on a voyage steeped in history aboard Cunard’s iconic ocean liner

Travel

Learn more about how to celebrate National Indigenous Peoples Day by visiting one of the many places in the country highlighting Indigenous culture

Travel

With its proximity to a number of small towns along the route, this Eastern Ontario trail is perfect for the seasoned walker looking for a not-too-rugged, wildlife-filled four-day hike

Travel

Robin Esrock recounts his experience rafting a tidal wave in Nova Scotia’s Shubenacadie River — the only place in the world to do so

Travel

Absorbing the spirit of the land through Indigenous-led tourism initiatives along B.C.’s Sunshine Coast

Travel

A music lover’s dream, this region of the U.S. is famous for its noteworthy strains of blues, soul and rock ‘n’ roll, plus the many music legends that were born here

Travel

Garbage litters the trail of the world’s most popular trek, but measures are being taken to clean up the Khumbu region — one kilogram at a time

Travel

A taste of North America’s best beer — plus where to eat, what to do and where to stay in Portland, Oregon

Travel

From catfish sandwiches to an Elvis-worthy lunch, these are some must-try spots in the music city of Tennessee

Travel

Seven sites in the birthplace of rock ‘n’ roll commemorate the city’s foundational role in the American civil rights movement

Travel

Playful wildlife, expansive beaches and spectacular cuisine are defining features of this waterfront town in the Florida Panhandle

Travel

An epic tour of the remote western Torngats appeals to adventure-seeking geography geeks, with treks via foot, boat and plane to explore the area’s geological and wildlife riches

Travel

A uniquely Canadian bucket list adventure featuring wildlife encounters, cultural history and custom-built experiences

Travel

The global explorer, adventurer, and TV host highlights his most dangerous experiences, regrets, what he has learned, and more

Travel

How a mutant grove of trees is adding mystery to the prairies