Travel

Tide and joy: New Brunswick’s culinary delights

From learning the secret of hand-dipping chocolate to dining on lobster aboard a cruise, New Brunswick’s growing food scene boasts plenty of new culinary experiences

- 622 words

- 3 minutes

Travel

From learning the secret of hand-dipping chocolate to dining on lobster aboard a cruise, New Brunswick’s growing food scene boasts plenty of new culinary experiences

Travel

Discovering beauty and resilience on the world’s second-largest barrier reef

Travel

Named after the south star, Octantis is Viking’s first expedition ship, which incorporates visits to Indigenous communities, supports environmental protection and more

Travel

From sea caves to deserts, this three-day guide offers the perfect itinerary to make the most of this corner of California

Travel

The first Marriott-branded all-inclusive resort offers outstanding hospitality and exquisite food options in a beloved sun destination

Travel

Robin Esrock investigates the growing trend of alcohol-free wine, beer and spirits

Travel

From snowshoeing on a frozen river to soaring over snow-covered mountains in a helicopter, here’s how to make the most of a family winter getaway in this spectacular region on the north shore of the St. Lawrence

Travel

Mount Engadine Lodge is the perfect base for a slew of spectacular mountain trails

Travel

A pilgrimage to Kejimkujik reveals centuries-old connections between descendants of Nova Scotia’s first Scottish settlers and the Mi’kmaq who saved them

Travel

A five-night, four-day adventure through Québec’s Gaspé Peninsula, full of mountain peaks, sweeping landscapes and close moose encounters

Travel

With its proximity to a number of small towns along the route, this Eastern Ontario trail is perfect for the seasoned walker looking for a not-too-rugged, wildlife-filled four-day hike

Travel

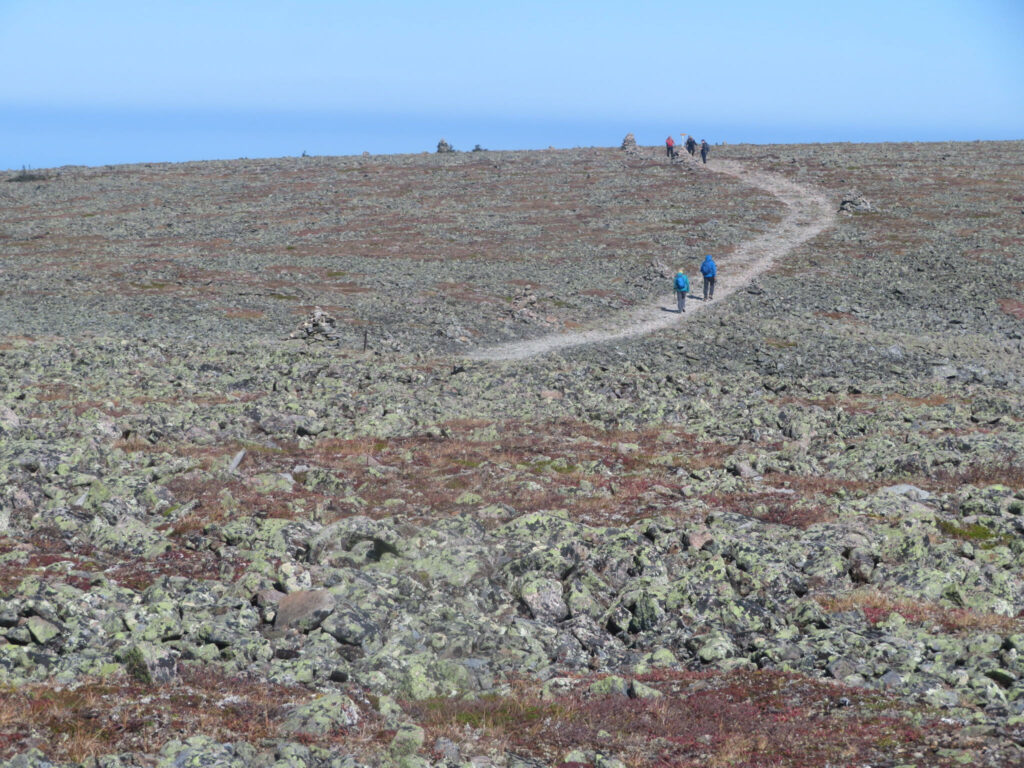

An ancient Mi’gmaq migration route that follows the Nepisiguit River’s winding route to the salt waters of Chaleur Bay, the Nepisiguit Mi’gmaq Trail is now one of the world’s best adventure trails

Travel

A tired mom’s quest for rest on a solo road trip around southern Vancouver Island

Travel

Here & There host and producer Liz Beatty tests her own mettle on backcountry peaks with CMH Heli Skiing and Summer Adventures. Along the way, she introduces us to some amazing women who’ve helped make mountaineering what it is today.

Travel

Robin Esrock reports on a bucket list experience with Canadian Geographic Adventures horseback riding in Banff National Park

Travel

Brian and Dee Keating share their incredible rafting journey in the remote Arctic tundra on a once-in-a-lifetime Canadian Geographic Adventure

Travel

The RCGS Explorer-in-Residence shares his experience travelling through Alaska with Cunard

Travel

Explorer-in-Residence Jill Heinerth discusses her time aboard Cunard’s Queen Elizabeth to Alaska

Travel

Travel

Travel

Travel

Travel

Travel

Travel

Experiencing the world’s largest carnival during a week of celebration, social unity, parades, colourful fashion and of course, partying

Travel

Seeing iconic landscapes before they fade away may be accelerating their demise. Can we square the circle on making these trips sustainable?

Travel

Recently renovated and renamed, the Lodge at Bow Lake (formerly Num-Ti-Jah Lodge) immerses guests in the history of Rocky Mountain exploration

Travel

Offering something for everyone, this 584-kilometre wind-swept shoreline is packed with historical sites, isolated beaches, quiet seaside towns and more

Travel

The ultimate rainforest retreat complete with eco-adventures, hands-on education and adrenaline-inducing activities amidst tropical jungle scenery

Travel

On the coast of B.C.’s mainland awaits an immersive experience on the water’s edge, where tourism can be an act of reconciliation

Travel

Photographer Jenny Wong reveals Newfoundland’s jaw-dropping scenery on an adventure with Great Canadian Trails

Travel

Navigating chunks of ice in frigid temperatures, Robin Esrock recounts his thrilling experience ice canoeing on the St. Lawrence River

Travel

RCGS Travel Ambassador Carol Patterson recounts her experience observing these legendary birds on a Canadian Geographic Adventure

Travel

Discover why Piedmont in northwestern Italy is a haven for gourmands

Travel

Oyster shucking, baskets of lobster and caesars galore, Prince Edward Island’s annual shellfish festival is the event for seafood lovers across the globe

Travel

Home to more than just legendary country music venues, Nashville also features some of the best food and drink in Tennessee

Travel

Friendly locals, tide-to-table seafood and some of the best fishing in Florida. Why Destin should be your next stop along the Florida Panhandle

Travel

Now on its sixth season, this popular cooking show combines Indigenous and French cuisine while exploring culture, tradition and good food

Travel

Travel

Travel

Travel

Travel

Travel

Travel

Travel

Travel

Travel

Travel

Travel

Travel

Once an enormous coral reef, these magnificent mountains are now one of Italy’s main outdoor attractions

Travel

Les villes et villages situés le long de la Promenade du sentier Fundy s’associent pour donner la priorité à la communauté et à l’environnement, alors que la région partage ses paysages enchanteurs avec le monde entier.

Travel

Cities and towns along the Fundy Trail Parkway are banding together to prioritize community and the environment as they share their magical landscape with the world

Travel

From slopes to ski lift passes and resorts to spas, the cost of a ski trip to Switzerland isn’t much more expensive than a visit to the Rockies

Travel

A taste of North America’s best beer — plus where to eat, what to do and where to stay in Portland, Oregon

Travel

An exclusive look at SailGP aboard Canada’s F50 catamaran yacht and how this international sailing competition is keeping sustainability in mind

Travel

With solar activity expected to peak in 2024, there’s never been a better time to see the northern lights. Here’s how to do it in the “aurora capital of North America.”

Travel

After years of waiting to see the aurora borealis, Robin Esrock recounts his experience viewing these dancing lights with his father in Yellowknife

Travel

Microdosing psilocybin, plus three other ways to relax and unwind by the crystal-clear waters of western Jamaica

Travel

A history of Alberta’s quirky Burger Baron restaurant chain

Travel

Susan Nerberg embarks on a deeply personal tour of Tromsø, taking part in Sámi Week as a means to better understand her own Sámi roots and culture

Travel

From modern works of sculpture to remnants of ancient civilizations, Italy’s Umbria region is rich in cultural heritage

Travel

Experiencing living history at Métis Crossing, a one-of-a-kind destination for Métis people to share Métis stories

Travel

Where to stay, what to do and how to make the most out of your time in Costa Navarino

Travel

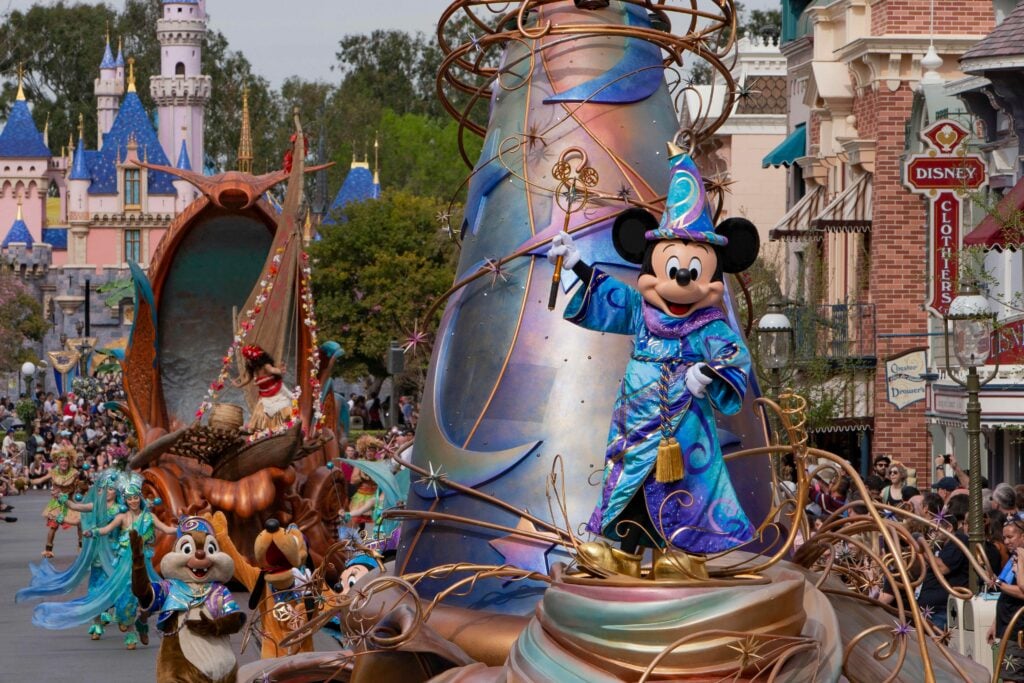

How to make the most out of your visit to Disneyland, plus all the tips and tricks needed to ensure you and your family have a positive experience

Travel

Rocking and rolling across the Atlantic on a voyage steeped in history aboard Cunard’s iconic ocean liner

Travel

Learn more about how to celebrate National Indigenous Peoples Day by visiting one of the many places in the country highlighting Indigenous culture

Travel

Robin Esrock recounts his experience rafting a tidal wave in Nova Scotia’s Shubenacadie River — the only place in the world to do so

Travel

Absorbing the spirit of the land through Indigenous-led tourism initiatives along B.C.’s Sunshine Coast

Travel

A music lover’s dream, this region of the U.S. is famous for its noteworthy strains of blues, soul and rock ‘n’ roll, plus the many music legends that were born here

Travel

Garbage litters the trail of the world’s most popular trek, but measures are being taken to clean up the Khumbu region — one kilogram at a time

Travel

From catfish sandwiches to an Elvis-worthy lunch, these are some must-try spots in the music city of Tennessee

Travel

Seven sites in the birthplace of rock ‘n’ roll commemorate the city’s foundational role in the American civil rights movement

Travel

Playful wildlife, expansive beaches and spectacular cuisine are defining features of this waterfront town in the Florida Panhandle

Travel

From New York’s iconic Statue of Liberty to the famous Christ the Redeemer in Rio de Janeiro, these are some of the world’s most captivating statues

Travel

A three-day guide to exploring the diverse culture, rich history and beautiful beaches of America’s first settlement

Travel

Following the St. Lawrence’s winding course through Quebec delivers a feast of history, culture and food

Travel

Night skiing under the direction of Olympic legend Nancy Greene Raine

Travel

The global explorer, adventurer, and TV host highlights his most dangerous experiences, regrets, what he has learned, and more

Travel

*Okay, just six — but it’s a start toward exploring this expansive border-straddling region of rocky islands, sparkling coves and hidden history

Travel

Fly fishing for steelhead trout and salmon in Northern B.C.’s bucket list angling destination

Travel

Wine, cheese and all the rest: highlights from Quebec’s sustainable culinary industry

Travel

At British Columbia’s Purcell Mountain Lodge, guests can partake in skiing and snowshoeing and then end the day with a well-deserved three-course dinner

Travel

How a mutant grove of trees is adding mystery to the prairies